My colleague Robyn Brentano at the Garrison Institute recently shared a Buddhist parable with me, which is retold in the book Eight Steps to Happiness by the renowned teacher, Geshe Kelsang Gyatso:

In Tibet there was once a famous Dharma practitioner called Geshe Ben Gungyal, who neither recited prayers nor meditated in the traditional posture. His sole practice was to observe his mind very attentively and counter delusions as soon as they arose. Whenever he noticed his mind becoming even slightly agitated, he was especially vigilant and refused to follow any negative thoughts. For instance, if he felt self-cherishing was about to arise, he would immediately recall its disadvantages, and then he would stop this mind from manifesting by applying its opponent, the practice of love. Whenever his mind was naturally peaceful and positive he would relax and allow himself to enjoy his virtuous states of mind.

To gauge his progress he would put a black pebble down in front of him whenever a negative thought arose, and a white pebble whenever a positive thought arose, and at the end of the day he would count the pebbles. If there were more black pebbles he would reprimand himself and try even harder the next day, but if there were more white pebbles he would praise and encourage himself. At the beginning, the black pebbles greatly outnumbered the white ones, but over the years his mind improved until he reached the point when entire days went by without any black pebbles. Before becoming a Dharma practitioner, Geshe Ben Gungyal had a reputation for being wild and unruly, but by watching his mind closely all the time, and judging it with complete honesty in the mirror of Dharma, he gradually became a very pure and and holy being. Why can we not do the same?

I’ve been thinking a lot about this story lately, as I’ve been undertaking a learning journey with an iPhone app called Expereal.

The program is a sort of 21st-century update on Gungyal’s pebbles, intended to promote self-reflection. Once installed, at regular intervals throughout the day, Expereal asks you a simple question:

“How are you feeling right now?”

In response, you turn an onscreen dial, providing a subjective rating from 1 to 10. As you move your finger, a corresponding inkblot grows in size and color on the screen, from a subdued blue dot to a bursting crimson splash. (The precise meaning of these kinesthetic ratings is left for you to decide.)

Your responses can be further annotated with notes and photos detailing where you were when you made them, and with whom. Expereal also allows you to chart your assessments over time, and (of course!) compare yourself to friends and fellow users:

The app owes much to its conceptual forebears, like designer Nicholas Felton’s personal “annual reports”, in which he details various aspects of his experiences and interactions with people over the course of a year, and to various other Quantified Self efforts.

But there is something qualitatively different here, and it starts with nature of the question itself. How often do we actually, genuinely attend to our own feelings? (An A-type New York friend joked, “I can’t do that and keep living here.”) How often do we seriously ask others how they’re feeling, or get asked in return? Once a day? Once a week? And how well do we remember how we were feeling last Tuesday? Last month? Last year? Like the inky stains on the wineglasses after a party, these countless subjective states have somehow left their traces in us, but who can remember the taste?

Unfortunately, being given the opportunity to answer the question doesn’t necessarily mean that one will do a good job actually answering it, especially at the beginning. The first hundred or so times Expereal asked me how I was feeling, my assessments were the kinds of superficial ones you might respond with if a stranger asked you on the street: “I’m fine.”, “All good.”, “Frustrated by a supermarket line.” Reviewing my answers after the first few weeks, it dawned on me: I had been politely lying to my smartphone. There’s a humbling moment.

So I recommitted to answering the question less glibly. How was I feeling right now?

The ‘real’ answers were harder to get to, and often more surprising when they arrived. Much of the time, I didn’t really know what I was feeling – it was hard to pin down what largely felt like an ephemeral mishmash. Expereal rarely found me living in the present moment – usually, my mind was occupied with a chorus of distant concerns or distractions. In the middle of a conversation, Expereal made me realize I wasn’t listening at all to my partner, or to myself, at all – I was just waiting, bored and impatiently, for my turn to speak. Ouch.

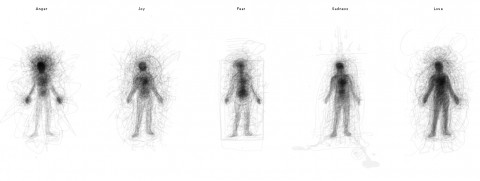

Pushing past such uncomfortable observations meant taking a short break, and attending more carefully and more holistically. And with practice I got better. I began to observe that whatever I was feeling, I was rarely feeling it just in my mind, it was in my body, too. – not just my hands, but my posture, the way I held my frame. I was reminded of a wonderful PopTech talk by the Irish designer Orlaugh O’Brien, about her project “Emotionally}Vague”, in which she collected and overlayed hundreds of people’s self-reported drawing of where they felt various emotions in their bodies:

The aggregate picture that emerged in the project is striking. People reported that anger was ‘felt’ in the head and hands, while love, by contrast, was felt all over. “Anger is a force, love is field,” said O’Brien. I certainly found the same.

More subtly still, I began to see how much of my own cognition was enactive, inextricably bound up in loops of perception and action, intimately connected to the systems that govern every modern life, including ones I had invented and taken on for my own purposes. The taxi, the railway station, the flickering of a neon light, the obligations to family and profession and countless other systems, objects and ideas all cycle through me continuously, leaving their stain, shaping my cognition and sense of self, in ways I had rarely attended to in the moment.

Answering the “How do you feel right now?” question over and over again has had other effects as well. It’s encouraged at least a little more generosity in me, made me modestly more likely to ask others how they are feeling, and ready to attend more carefully to the answers. Attending builds awareness, and awareness in turn is the pretext for empathy, generosity and equanimity.

~

Expereal is available on iTunes for free. You can read an interview with its creator, Jonathan Cohen, here. Note: a Facebook login is required to use the program.

Image Credit: Cy Twombly, Untitled (Roses) Gaeta, 2008