This essay appears today on the website of the Harvard Business Review:

This July, aviation officials released their final report on one of the most puzzling and grim episodes in French aviation history: the 2009 crash of Air France Flight 447, en route from Rio de Janeiro to Paris. The plane had mysteriously plummeted from an altitude of thirty-five thousand feet for three and a half minutes, before colliding explosively with the vast, two-mile-deep waters of the south Atlantic. Two hundred and twenty eight people lost their lives; it took almost two years, and the help of robotic probes from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute to even find the wreckage. The sea had swallowed them whole.

What — or who — was to blame? French investigators identified many factors, but singled out one all-too-common culprit: human error. Their report found that the pilots, although well-trained, had fatally misdiagnosed the reasons that the plane had gone into a stall, and that their subsequent errors, based on this initial mistake, led directly to the catastrophe.

Yet it was complexity, as much as any factor, which doomed Flight 447. Prior the crash, the plane had flown through a series of storms, causing a buildup of ice that disabled several of its airspeed sensors — a moderate, but not catastrophic failure. As a safety precaution, the autopilot automatically disengaged, returning control to the human pilots, while flashing them a cryptic “invalid data” alert that revealed little about the underlying problem. Confronting this ambiguity, the pilots appear to have reverted to rote training procedures that likely made the situation worse: they banked into a climb designed to avoid further danger, which also slowed the plane’s airspeed and sent it into a stall.

Confusingly, at the height of the danger, a blaring alarm in the cockpit indicating the stall went silent — suggesting exactly the opposite of what was actually happening. The plane’s cockpit voice recorder captured the pilots’ last, bewildered exchange:

(Pilot 1) Damn it, we’re going to crash… This can’t be happening!

(Pilot 2) But what’s happening?

Less than two seconds later, they were dead.

Researchers find echoes of this story in other contexts all the time — circumstances where adding safety-enhancements to systems actually makes crisis situations more dangerous, not less so. The reasons are rooted partly in the pernicious nature of complexity, and partly in the way that human beings psychologically respond to risk.

We rightfully add safety systems to things like planes and oil rigs, and hedge the bets of major banks, in an effort to encourage them to run safely yet ever-more efficiently. Each of these safety features, however, also increases the complexity of the whole. Add enough of them, and soon these otherwise beneficial features become potential sources of risk themselves, as the number of possible interactions — both anticipated and unanticipated — between various components becomes incomprehensibly large.

This, in turn, amplifies uncertainty when things go wrong, making crises harder to correct: Is that flashing alert signaling a genuine emergency? Is it a false alarm? Or is it the result of some complex interaction nobody has ever seen before? Imagine facing a dozen such alerts simultaneously, and having to decide what’s true and false about all of them at the same time. Imagine further that, if you choose incorrectly, you will push the system into an unrecoverable catastrophe. Now, give yourself just a few seconds to make the right choice. How much should you be blamed if you make the wrong one?

CalTech system scientist John Doyle has coined a term for such systems: he calls them Robust-Yet-Fragile — and one of their hallmark features is that they are good at dealing with anticipated threats, but terrible at dealing with unanticipated ones. As the complexity of these systems grow, both the sources and severity of possible disruptions increases, even as the size required for potential ‘triggering events’ decreases — it can take only a tiny event, at the wrong place or at the wrong time, to spark a calamity.

Variations of such “complexity risk” contributed to JP Morgan’s recent multibillion-dollar hedging fiasco, as well as to the challenge of rebooting the US economy in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. (Some of the derivatives contracts that banks had previously signed with each other were up to a billion pages long, rendering them incomprehensible. Untangling the resulting counterparty risk — determining who was on the hook to whom — was rendered all but impossible. This in turn made hoarding money, not lending it, the sanest thing for the banks to do after the crash.)

Complexity is a clear and present danger to both firms and the global financial system: it makes both much harder to manage, govern, audit, regulate and support effectively in times of crisis. Without taming complexity, greater transparency and fuller disclosures don’t necessarily help, and might actually hurt: making lots of raw data available just makes a bigger pile of hay in which to try and find the needle.

Unfortunately, human beings’ psychological responses to risk often makes the situation worse, through twin phenomena called risk compensation and risk homeostasis. Counter-intuitively, as we add safety features to a system, people will often change their behavior to act in a riskier way, betting (often subconsciously) that the system will be able to save them. People wearing seatbelts in cars with airbags and antilock brakes drive faster than those who don’t, because they feel more protected — all while eating and texting and God-knows-what-else. And we don’t just adjust perceptions of our own safety, but of others’ as well: for example, motorists have been found topass more closely to bicyclists wearing helmets than those that don’t, betting (incorrectly) that helmets make cyclists safer than they actually do.

A related concept, risk homeostasis, suggests that, much like a thermostat, we each have an internal, preferred level of risk tolerance — if one path for expressing one’s innate appetite for risk is blocked, we will find another. In skydiving, this phenomenon gave rise, famously, to Booth’s Rule #2, which states that “The safer skydiving gear becomes, the more chances skydivers will take, in order to keep the fatality rate constant.”

Organizations also have a measure of risk homeostasis, expressed through their culture.

People who are naturally more risk-averse or more risk tolerant than the culture of their organizations find themselves pressured, often covertly, to “get in line” or “get packing.”

This was well in evidence at BP, for example, long before their devastating spill in the Gulf — the company actually had a major accident somewhere in the world roughly every other year for a decade prior to the Deep Water Horizon catastrophe. During that period, fines and admonitions from governments came to be seen by BP’s executive management as the cost of growth in the high-stakes world of energy extraction — and this acceptance sent a powerful signal through the rank-and-file. According to former employees at the company, BP’s lower-level managers would instead focus excessively on things like the dangers of not having a lid on a cup of coffee, rather than the risk and expense of capping a well with inferior material.

Combine complex, Robust-Yet-Fragile systems, risk-compensating human psyches, and risk-homeostatic organizational cultures, and you inevitably get catastrophes of all kinds: meltdowns, economic crises, and the like. That observation is driving increasing interest in the new field of resilience — how to build systems that can better accommodate disruptions when they inevitably occur. And, just as vulnerabilities originate in the interplay of complexity, psychology and organizational culture, keys to greater resilience reside there as well.

Consider the problem of complexity and financial regulation. The elements of Dodd-Frank that have been written so far have drawn scorn in some quarters for doing little about the problem of too-big-to-fail banks; but they’ve done even less about the more serious problem of too-complex-to-manage institutions, not to mention the complexity of the system as a whole.

Banks’ advocates are quick to point out that many of the new regulations are contradictory, confusing and actually make things worse, and they have a point: adding too-complex regulation on top of a too-complex financial system could put us all, in the next crisis, in the cockpit of a doomed plane.

But there is an obvious, grand bargain to be explored here: to encourage the reduction in the complexity of both firms and the financial system as a whole, in exchange for reducing the number and complexity of regulations with which the banks have to comply. In other words, a more vanilla, but less over-regulated system, which would be more in line with its original purpose. Such a system would be easier to police and tougher to game.

Efforts at simplification also have to deal urgently with the problem of dense overconnection — the growing, too-tight “coupling” between firms, and between international financial hubs and centers. In 2006, the Federal Reserve invited a group of researchers to study the connections between banks by analyzing data from the Fedwire system, which the banks use to back one another up. What they discovered was shocking: Just sixty-six banks — out of thousands — accounted for 75 percent of all the transfers. And twenty five of these were completely interconnected to one another, including a firm you may have heard of called Lehman Brothers.

Little has been done about this dense structural overconnection since the crash, and what’s true within the core of the financial sector is also true internationally. Over the past two decades, the links between financial hubs like London, New York and Hong Kong have grown at least sixfold. By reintroducing simplicity and modularity back into the system, a crisis somewhere doesn’t always have to become a crisis everywhere.

Yet, no matter the context, taking steps to tame complexity of a system are meaningless without also addressing incentives and culture, since people will inevitably drive a safer car more dangerously. To tackle this, organizations must learn to improve the “cognitive diversity” of their people and teams — getting people to think more broadly and diversely about the systems they inhabit. One of the pioneers in this effort is, counterintuitively, the U.S. Army.

Today’s armed forces confront circumstances of enormous ambiguity — theatres of operation with many different kinds of actors — NGOs, civilians, partners, media organizations, civilian leaders, refugees, and insurgents alike are mixed together, without a “front line.” In such an environment, the cultural nuances of every interaction matter, and the opportunities for misunderstanding signals is extremely high. In the face of such complexity, it can be powerfully tempting for tight-knit groups of soldiers to fall back on rote training, which can mean blowing things up and killing people. Making one kind of mistake might get you killed, making another might prolong a war.

To combat this, retired army colonel Greg Fontenot and his colleagues at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, started the University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies, more commonly known by its nickname, Red Team University. The school is the hub of an effort to train professional military “devil’s advocates” — field operatives who bring critical thinking to the battlefield and help commanding officers avoid the perils of overconfidence, strategic brittleness, and groupthink. The goal is to respectfully help leaders in complex situations unearth untested assumptions, consider alternative interpretations and “think like the other” without sapping unit cohesion or morale, and while retaining their values.

More than 300 of these professional skeptics have since graduated from the program, and have fanned out through the Army’s ranks. Their effects have been transformational — not only shaping a broad array of decisions and tactics, but also spreading a form of cultural change appropriate for both the institution and the complex times in which it now both fights and keeps the peace.

Structural simplification and cultural change efforts like these will never eliminate every surprise, of course, but undertaken together they just might ensure greater resilience — for everyone — in their aftermath.

Otherwise, like the pilots of Flight 447, we’re just flying blind.

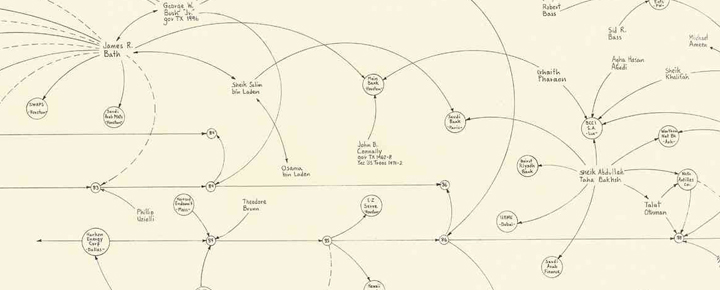

Image Credit: closeup of Mark Lombardi “George W. Bush, Harken Energy and Jackson Stephens c.1979-90”